Shopping at a mall is better for the environment than buying those same goods online, according to a study conducted by Deloitte and Simon. The research provides one of the most comprehensive comparisons to date of the two approaches to retail and, in its indictment of the environmental impact of e-shopping, may offer landlords a powerful marketing tool.

This was not necessarily Simon’s motivation in embarking on the research, according to Mona Benisi, Simon’s senior director of sustainability. Rather, she says, Simon wanted to learn more about where malls stood versus the Internet on sustainability.

“It just helps us understand the entire value chain and where we have opportunities to improve,” Benisi said. Over the past decade or so, Simon has reduced its overall energy usage by 32 percent but desired better data on the ways various shopping behaviors affect the environment, she says. “There had been previous studies done, but we felt they were not as comprehensive,” she said, “because they lacked the full-picture understanding of the consumer shopping journey at the mall.”

Those earlier studies typically compare the environmental effects of mall versus online shopping by citing scenarios in which shoppers buy a product from one or the other channel. The Simon study, published in March, factors in additional variables such as the types of cars people drive to the mall, the numbers of people making those trips in one vehicle and the possibility that they might combine their shopping trip with other errands. “A visit to the mall often includes other activities, such as dining, errands and other forms of entertainment,” the researchers write. “If done separately (either online or physically), these additional activities add more energy and fuel emissions.”

The objective was to determine how much fuel, electricity and packaging would be consumed if a shopper were to buy a common “basket” of four products — a women’s top, a pair of shoes, a coffeemaker and a set of wineglasses — from a mall or an online retailer. If every visitor to the typical mall were to buy this basket of items once in a year, the report holds, that would translate to a total of 14.3 million items. By the researchers’ calculations, the environmental impact in greenhouse gas-emissions terms of purchasing those same goods online would be 37,710 metric tons for malls, versus 40,295 for online.

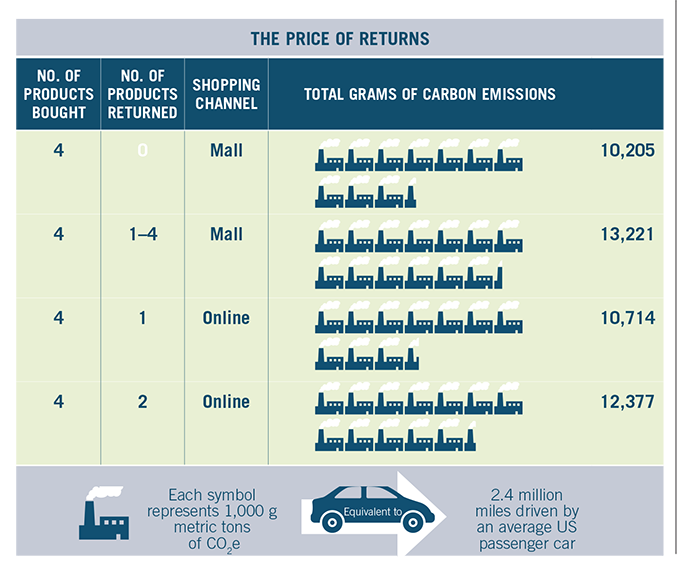

To get a sense of the e-commerce carbon footprint, the researchers performed calculations on several factors: the amount of fuel needed to ship goods from an online retailer’s distribution center to a local sorting facility; the amount of energy consumed by the data centers and the phones, computers and similar devices used in online orders; the required packaging; the fuel consumed in last-mile product delivery of such goods; and the amount of energy and fuel needed for any returns of those goods. Internet shopping turns out to be less efficient, according to the report, in part because shoppers typically return, on average, some 33 percent of online purchases, versus the 7 percent of returned items that were bought at malls. Likewise, the corrugated boxes and other forms of packaging required to get online orders shipped makes a greater impact on the planet than the use of shopping bags, the researchers write.

So should the rest of the industry try to gain a competitive edge against the Internet by touting these findings? According to some observers unaffiliated with the research, such a strategy could prove to be an uphill climb with consumers. “Simon is assuming that if they can prove that online shopping isn’t as sustainable as brick-and-mortar shopping, people are going to care, but I don’t think they do,” said Darrin Duber-Smith, a marketing professor at Metropolitan State University of Denver whose focus includes sustainable products. “Sustainability was big in the ’90s and 2000s. After the recession hit, it dropped to like 19th or 20th on people’s priority lists.” Similarly, Kenneth R. Richards, an Indiana University professor who studies environmental and energy policy, says green marketing tends to yield disappointing results relative to other messages. “When items are marketed as good for the environment, they have very little competitive advantage, as opposed to when they are marketed as safe,” he said.

A January 2015 survey of 300 shoppers by SCM World, a London-based supply-chain research and development firm, found that just 20 percent of respondents ranked sustainability as first or second in importance, according to Patrick Van Hull, the firm’s vice president of research. “The consumer is still largely driven by quality, price and the experience,” he said. “We will see consumers being conscious of their actions, but the extent to which that will drive their decisions is up for debate.”

Nonetheless, the questions asked in the study are still worth pondering, argues Richards, who reviewed and commented on the Simon white paper before its publication. “It is a thought-provoking and quite well-conceived study,” he said. The methodology employed appears to be fair, he asserts. “You always have to make some calls about what you’re going to measure and how you’re going to structure the comparisons, but I don’t see anything here that makes me uncomfortable,” Richards said.

In the conclusion to the report, the authors make a strong claim — that online shopping is worse for the environment — and argue that the negative -impact of online shopping is likely to get worse with time. “Put simply, the choices customers make regarding how they buy products and how they utilize product return options have clear impacts on the environmental footprint,” they write.

Benisi says the study underscores that Simon is on the right track with efforts to get customers and retailers engaged in the company’s fourfold sustainability strategy, which involves properties, retailers, consumers and communities. “What I hear from readers in general is: ‘Wow — I had no idea my choices mattered so much,’ ” said Benisi. “We were hoping to create more awareness that in the age of everywhere, anytime, anything shopping, your choices have an impact.”

As the white-paper researchers note, visiting a mall as a group will lower the overall environmental impact of a trip. Today the average size of a mall shopping group is 2.2 people, they write, so if landlords could boost that number by encouraging more people to carpool, the sustainability of brick-and-mortar properties would improve in tandem. Bringing about change would not be easy, but landlords could make a difference over time by highlighting the effects of various shopping behaviors, Richards suggests. For one thing, sustainability campaigns could encourage people to consider trying to consolidate their purchases into a single mall visit rather than making multiple trips, he says.

“If Simon could get the word out with a study like this and encourage people to be thoughtful in planning their mall trips, it could work to everyone’s advantage,” Richards said. Given greater awareness, online shoppers might well opt to avoid the common practice of ordering multiple items online with the intention of shipping most of them back after trying them on. “Just because returns are free, that does not mean they have no environmental impact, so people might start to pay more attention to that,” Richards said.

Indeed, the white paper highlights the relative inefficiency of online returns versus products returned to the mall. “Specifically, if shoppers buy four products online and return two because they do not fit or the color wasn’t right, the impact is more than 21 percent higher compared with buying the same products at the mall and not having to return them because they have been tried on,” the researchers write. “That’s a big difference.”

From a marketing standpoint, owners and managers should not be afraid to get the word out about their increasingly successful efforts to boost energy efficiency, says Barry Wood, a senior vice president and director of retail operations for JLL. “There is an opportunity to talk more about the things we’re doing in the industry to make our properties more sustainable and be good partners with the environment,” he said. Within JLL’s retail property portfolio, adoption of energy-saving LED lighting is taking off, Wood notes. “Even though the payback is not real fast, a lot of our owners are making the decision now to install LEDs,” he said. “They’re doing it not just based on the return on investment, but because it’s the right thing to do.”

Solar energy also is poised for faster growth among retailers and mall owners, Wood says. Ikea, for one, has set aside more than $2 billion for renewable-energy projects around the world. Aiming to become energy-independent by 2020, the Scandinavian furniture retailer has installed some 700,000 solar panels globally and owns approximately 260 wind turbines across Europe, Canada and the U.S. The Las Vegas Ikea store that was scheduled at press time for a May -opening boasts the largest single-use retail rooftop solar array in Nevada, according to a press release. The store’s 3,620 solar panels will offset 1,207 tons of carbon dioxide annually — equal to the average yearly emissions of 254 cars, according to the company. Though Ikea owns its solar panels, a growing number of retailers and landlords are likely to lease their rooftops to utilities for solar arrays in the years ahead, Wood says. “We want to rent our roofs — to continue to be landlords rather than get in the business of being an energy generator,” he said.

Ultimately, Simon’s research underscores the need for all stakeholders — owners, retailers, shoppers and local communities — to work together toward the common goal of protecting the environment, Benisi says. “The study just highlighted that to tackle sustainability topics in general,” she said, “you really need a holistic approach.”