Gridlocked roads, rickety bridges, overburdened transit systems and other infrastructure problems act as a significant drag on retail sales, experts say, even though this issue draws far less attention than the supposed threat posed by e-commerce. This is why a newly formed task force — organized and supported by ICSC’s Office of Global Public Policy — is focusing on the need for infrastructure projects that can spur development and make it easier for people to go out to shop and spend. Put together this spring, the 14-member task force is to hold its inaugural meeting on June 12, in Washington, D.C.

“It’s made up of a host of people from around the country with expertise in real estate development, infrastructure financing and other disciplines,” said April Anderson Lamoureux, who heads the task force and is president of Anderson Strategic Advisors, a Boston-based economic development firm. “Our task is to consider the state of U.S. infrastructure and seek opportunities for change that will support the retail and development sectors. We expect to continue this effort until we see a package of legislation introduced and passed through Congress.”

According to the American Society of Civil Engineers’ most recent Infrastructure Report Card, the cumulative letter grade for U.S. infrastructure is an eye-widening D-plus, based on the conditions of 16 infrastructure categories that ASCE charts every four years. This latest report, published in March 2017, does cite some encouraging progress in rail development and six other categories. But the U.S. must now invest nearly $4.6 trillion — about $2 trillion more than originally planned — if the country is to boost its grade to a B by 2025, the report’s authors write.

By ASCE’s calculations, inaction on distressed infrastructure already costs the typical American some $3,400 per year in lost disposable income, according to Brian Pallasch, the professional body’s managing director of government relations and infrastructure initiatives.

Getting crowded Commuters wait for train service to be restored at New York City's Grand Central Terminal on May 15, 2018, after a severe thunderstorm that downed trees, caused power outages and resulted in suspension of some Metro-North lines. A powerful storm swept through the region just as the evening commute was starting

“The average person is losing hundreds of dollars per year just sitting in traffic in an urban area,” he said. “Failing or underperforming infrastructure — whether it is traffic, power outages or leaky pipes losing millions of gallons of water every day — impacts families and businesses and hurts the economy overall.” According to the ASCE report, by 2025 this type of inaction will translate into about $3.9 trillion in U.S. GDP losses and some 2.5 million jobs lost. Along with taking money out of people’s pockets, infrastructure-related costs can force retailers to increase their prices, thus hurting consumers still more, says Pallasch. “If it costs Walmart that much more money to ship goods, they are ultimately going to pass it on to you and me,” he said.

But Lamoureux sees the task force mission as broader than merely pushing for greater spending on infrastructure. Given the sheer pace of change in American society, she says, it makes sense to review how the relationship between retail and infrastructure is changing as well. “ICSC is taking a step back and looking at different trends,” Lamoureux said. “We’re thinking, for instance, about challenges and opportunities for the retail sector as it relates to transit-oriented development. What can government do to help support more retail growth and development in and around transit nodes?”

In many urban markets around the country, the availability of mass transit is becoming increasingly important to the success of retail and mixed-use projects alike, observers say. “A lot of that has to do with the different demographic profile of the Millennial generation,” noted Lamoureux. “Millennials are less likely to own a vehicle, and they have more interest in walkable communities and public transit.”

“A third of the people filling out applications for those apartments don’t have driver’s licenses. Everything is going to mass transit”

In the New York City tristate area, for one place, the effects of this trend are already visible enough to developers, says Chase Welles, a broker and partner in the New York City office of the Atlanta-based Shopping Center Group. “I was talking to the developer of a 1,000-unit apartment complex in [the New York borough of Queens] recently, and he told me that a third of the people filling out applications for those apartments don’t have driver’s licenses,” Welles said. “Everything is going to mass transit.”

But while mass transit is well established in New York, the city’s aging subway system is notoriously overloaded and dilapidated, Welles points out. “It is a mob scene,” he said. “The existing system is running with signals from the 1950s and is at capacity. They can’t run the trains any closer together, because the signals are part of an old analog system, with someone flipping switches in a dark basement somewhere.” Replacing those signals could cost anywhere between $8 billion and $15 billion over a 10- or 15-year period, according to a plan reportedly under consideration by the New York City Transit Authority. Astronomical as those sums might sound, however, increasing numbers of New Yorkers now support rebooting the system, says Welles. “Everybody has realized that something needs to happen,” he said. “That is the first step toward progress.”

As task force members study these issues, they will be weighing the potential opportunities of reinvestment in existing transit systems as opposed to, say, only building more highways, according to Lamoureux. “It may be less expensive to invest in transit improvements and to develop the nodes around that transit,” she said. “If so, how can we make that happen in a more systemic way? And how can we help developers who want to do that [to] get shovels in the ground more quickly?”

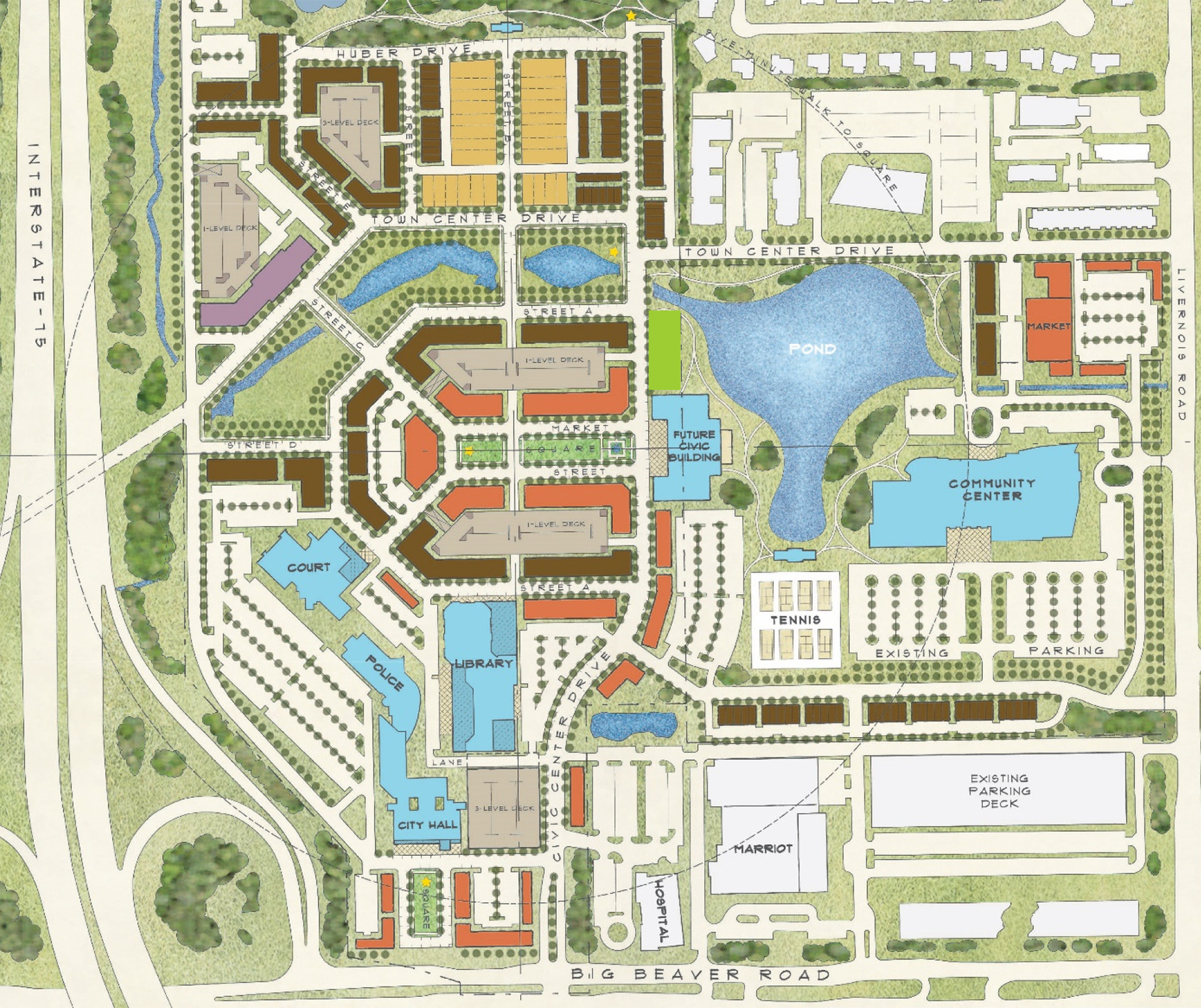

Municipal makeover Infrastructure concerns bedevil visionary redevelopments such as Troy (Mich.) Town Center, a 100-acre redevelopment of the Troy Civic Center with a mix of proposed uses, including about 200,000 square feet of retail

Along the same lines, says Lamoureux, the task force intends to look carefully at the effects on retail development of deferred maintenance on rundown or overtaxed roads, bridges, electrical grids, sewer systems and the like. Though plans to build a new subway system or suspension bridge would surely get all the headlines, the issue of deferred maintenance is nonetheless critical because of its potential to limit or even scuttle development projects, says Robert J. Gibbs, president of the Birmingham, Mich.–based Gibbs Planning Group, which specializes in urban retail planning and development. “There has been a lot of delayed maintenance, and a lot of delayed improvements, around the country,” he said. “Projects often stall because of a public perception that they will generate more traffic than the roads can handle, even though this is often not true.”

That happened last year, when the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority canceled a $200 million development planned for its Brookhaven station, recalls architect Angelo A. Carusi, a task force member who is principal of the Cooper Carry retail group. “The MARTA station itself, which was an infrastructure investment from 30 or 40 years ago, provided this great opportunity for development,” Carusi said. “But traffic was one of the issues that was difficult to overcome.” Deferred maintenance on the DeKalb County sewer system was another infrastructure issue that emerged, he notes. “A lot of people in the community didn’t believe the system could handle the waste from this development, even though we received confirmation from the county,” Carusi said.

Gibbs’ vision for Troy (Mich.) Town Center — a 100-acre redevelopment of the Troy Civic Center with a mix of proposed uses, including about 200,000 square feet of retail — has called for between 2,500 and 3,000 residential units. But those plans may have to be scaled back, he says, because of infrastructure-related constraints. “In the due diligence, the city found out that the sewer capacity could only accommodate about 800 residential units,” Gibbs said. “That was a big drop in what we wanted, because in this kind of planning — for walkable town centers — more is more: The more people who live there, the better the restaurants do, and the livelier it is.” City officials are now studying the viability of replacing those pipes, Gibbs says.

“When officials in municipalities with overtaxed or eroding infrastructure are reviewing new projects, they often ask the developer to foot the bill for things that need fixing”

For developers, deferred maintenance can pose a challenge in other ways: When officials in municipalities with overtaxed or eroding infrastructure are reviewing new projects, they often ask the developer to foot the bill for things that need fixing, Lamoureux says. “I am from Massachusetts, and that is a very big issue here, because we have some of the oldest infrastructure in the country,” she said. Moving forward, the task force will seek opportunities to work with federal and state officials to reduce this burden on private-sector developers. “We’ll be taking a hard look at this to find a path forward,” Lamoureux said. “There are certainly creative solutions out there to be found.”

To find those new approaches, the task force will look at innovative development projects, incentives programs and public-private partnerships at the state level. Ideally, they will find solutions that could scale nationally, Lamoureux says. Fortunately, the members should have plenty to study, thanks to the robust level of infrastructure-related activity in many states over the past few years, says Pallasch. “We are at 26 states now in the last five years that have increased [infrastructure spending] in some form or fashion,” he said. “They have increased their transportation funding through legislative action and governor signatures. We are seeing real progress.”

Georgia is one example. In May Gov. Nathan Deal signed legislation geared toward laying the groundwork for massive expansion of mass transit in gridlocked metro Atlanta. Under the law, 13 counties gained the right to raise billions of dollars for transit by levying sales taxes for up to 30 years. The measure also established a board to coordinate the construction and financing of transit projects. “People in [metro Atlanta] have finally gotten fed up with the gridlock,” said Carusi, who is based in Atlanta. “They are starting to understand that we cannot just build more roads to get out of it.”

Iconic example Projects like the High Line, an elevated park, greenway and rail trail on New York City’s West Side, continue to prove the value of infrastructure projects in spurring retail, restaurants and other economic activity

Meanwhile, projects like the High Line, an elevated park, greenway and rail trail on New York City’s West Side, continue to prove the value of infrastructure projects in spurring retail, restaurants and other economic activity, says Welles. “The High Line was done with tax increment financing, and it really worked,” he said. “Now there’s a proposal to build a trolley along the waterfront connecting [the boroughs of] Brooklyn and Queens. It’s a big infrastructure project that could bring whole new access for commuters and tourists — and for retail — to a historically neglected part of New York.”

But while some are sanguine about progress at the state level, the federal government will still have to be a good partner, Pallasch says. “The federal government has not stepped up in what I would call a complementary fashion in terms of increasing infrastructure investment,” he said. “We feel pretty strongly that a core function of the federal government should be improving interstate commerce. That means making sure that our roads, airports, seaports — all of those things — work efficiently. It is terribly important.”

Bureaucracies, too, could promote better infrastructure by ramping up their efficiency, says Lamoureux, who previously served as Massachusetts’ assistant secretary for economic development, with a focus on infrastructure. Often, merely getting a straight yes-or-no answer from a government agency can be frustratingly difficult, she says, and developers are often forced to jump through too many bureaucratic hoops to gain financing help on infrastructure projects. “We will be looking to see if there are opportunities to break down barriers and better expedite and coordinate approvals,” Lamoureux said. “The lead time doesn’t have to be so long. My motto is, ‘Streamline everything.’ ”

In addition to beneficial policy shifts that are relatively straightforward, the task force will also be paying attention to the long-term picture — everything from driverless cars to so-called smart cities, Lamoureux says. “We do not have all of the answers yet,” she said, “but I’m very optimistic that we’re going to eventually have a full set of recommendations that will be bipartisan [and] attractive to our federal leaders and that we’ll have some success getting through Congress on behalf of ICSC’s members.”

By Joel Groover

Contributor, Commerce + Communities Today