COVID-19 is giving states and counties their toughest economic test in modern history: dwindling revenue thanks to evaporating retail sales alongside increasing expenses going toward public services. All told, states and counties collected about $1.6 trillion in taxes in 2019, according the U.S. Census Bureau. Property and sales taxes make up about 55 percent of local general revenue, according to the Urban Institute, and shopping centers alone are responsible for 5.1 percent of state and local property taxes, according to ICSC Research.

States, counties and municipalities use their revenue to provide essential services like police and fire protection, as well as social safety nets for their residents. Property taxes are generally paid semiannually while sales taxes are collected monthly. The good news is that in general, most states and counties are entering this period in decent financial shape. According to the National Association of State Budget Officers, states ended the last fiscal year with $72 billion in rainy-day funds, or 7.6 percent of their general funds. Just before the Great Recession in 2008, by comparison, state coffers had amassed $33 billion in rainy-day funds, or about 4.7 percent of total funds.

Still more good news: Some financial relief is on the way. Under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act that Congress passed in March, counties and states will receive $150 billion in federal aid. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve has pledged to support the municipal bond market, a primary source of lending for county and local governments.

The big unknown is how long local governments can weather an economic shutdown. “These are uncharted waters for local governments, so having sufficient cash reserves and implementing expense management will be important to carry us through the down times,” said Brian O’Leary, a consultant who’s worked for Simon, GGP, JLL and most recently for Loyola University, as senior asset manager. “Recalibrating sales tax revenue and property tax income will be a challenge for small towns, as the new normal is unknown at this time.”

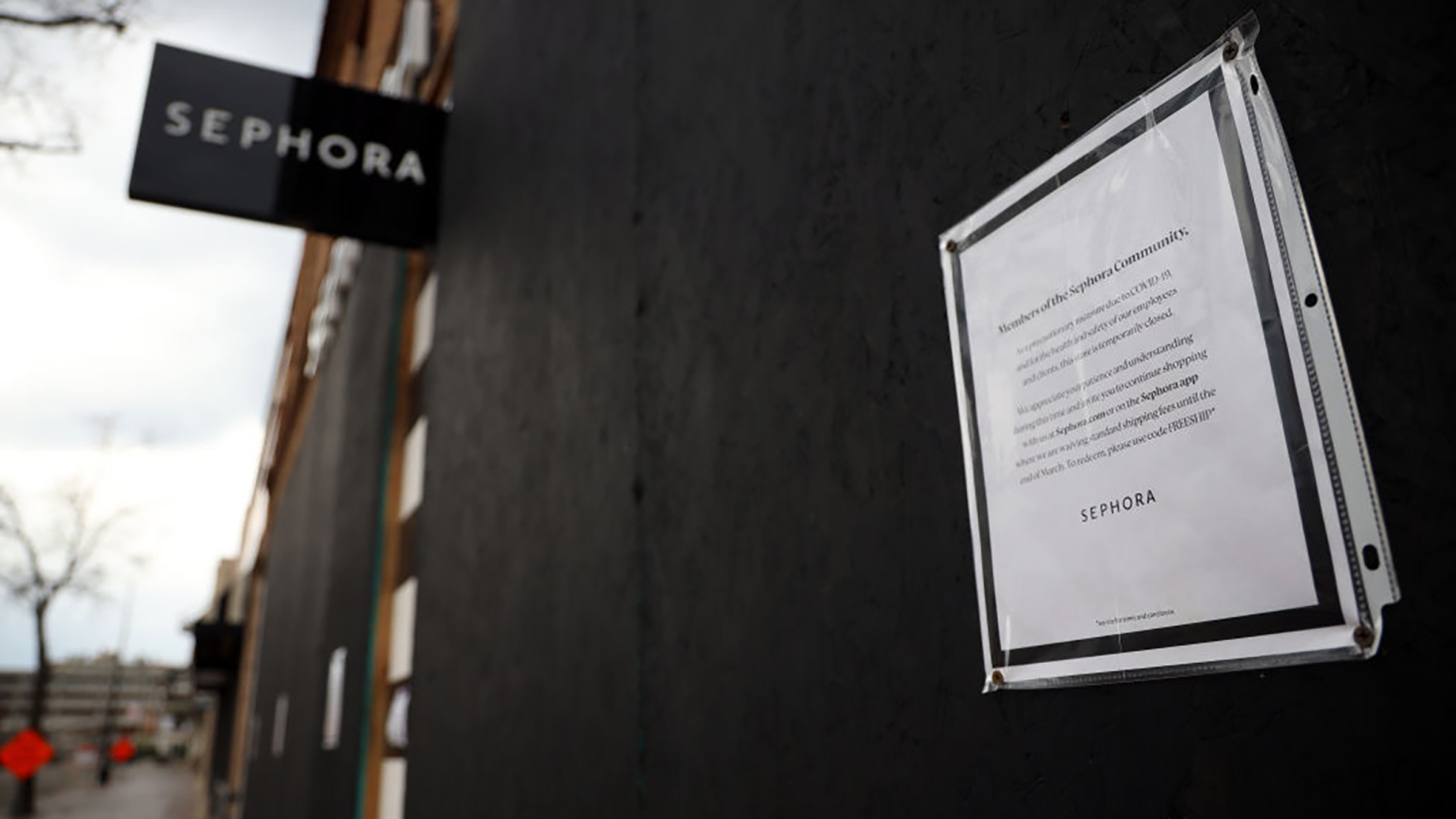

A closed sign on the boarded-up entrance of the Sephora store at Country Club Plaza, in Kansas City, Missouri. The center is usually bustling but now sits virtually empty in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic

Cities, counties and states finalize their annual budgets early in the year. Many cities, such as Philadelphia, must pass a balanced budget by the beginning of the fiscal year. For Philadelphia, that will be July 1. “Having a reduction of sales tax revenue is a big issue and concern for our city,” said Derek Green, chair of the Philadelphia City Council’s finance committee. The city’s original budget was drafted on March 5, and a revised budget is now expected to be presented on May 1. Green said that under normal conditions, a new budget would be working its way through hearings.

Leading into this budget season, Philadelphia had a general fund balance of about $400 million. “We are now looking at a greatly reduced fund balance, and that is going to impact us going forward, especially the loss of sales taxes, as well as loss of other taxes coming into the city of Philadelphia,” he said. “This is going to be a big concern for us, and we are going to have to really make some hard decisions when we receive the new budget.”

“These are uncharted waters for local governments”

The city created a special grant and loan-relief fund to help local small businesses and sent letters asking local lenders to provide forbearance for business owners and individuals. It also is working with businesses to push back tax deadlines whenever possible. For example, the deadline for filing real estate taxes has been delayed 30 days to April 30. “I have had conversations with organizations to reach out to banks at a national level to see what type of relief they can give to various businesses or organizations or properties like shopping center owners to deal with some of the challenges of not having revenue come into their stores and for tenants,” said Green.

While many retailers have shifted to delivery and online models, that revenue is unlikely to mitigate their sales shortfalls. “While online shopping can pick up some slack, 88.6 percent of retail sales were still at brick-and-mortar stores as of the last quarter of 2019,” said Anjee Solanki, national director of retail services in the U.S. for Colliers International. And the retailers that are allowed to remain open don’t sell many products that can be taxed. Groceries, for example, are considered essential items and are not taxable in most states, though Illinois taxes them at 1 percent.

During typical economic downturns, state and local governments look at three options to balance their budgets, according to Lucy Dadayan, senior research associate at the Urban Institute: raising tax rates, cutting spending and tapping into rainy-day funds. “It will be hard to raise tax rates during the public health crisis,” said Dadayan, “and while local governments can look into cutting non-essential spending areas, that won’t help much in addressing revenue shortfalls and substantial growth in spending, largely caused by the substantial growth in health care costs. Tapping rainy-day funds where possible would be necessary. Fortunately, state and local governments are getting some aid from the federal government, but that’s not going to be enough.”

Sales taxes

Forty-five states collect statewide sales taxes, and the District of Columbia collects them districtwide. Local sales taxes are collected in 38 states, and many of those rates rival or exceed state rates. “In general, state and local governments that have high reliance on sales tax revenues will see a larger impact of the shutdown of services and businesses,” said Dadayan.

California has the highest state-level sales tax rate, at 7.25 percent, followed by Indiana, Mississippi, Rhode Island, and Tennessee. The five states with the highest average local sales tax rates are Alabama, at 5.22 percent, followed by Louisiana, Colorado, New York, and Oklahoma.

Thanks to a robust U.S. economy, sales tax collections have been rising for years. For example, local sales taxes in the state of New York totaled $18.3 billion in 2019, up $815 million, or 4.7 percent, from 2018.

Property taxes

“We have been pushing for state and local governments to find ways to allow our members to keep their lights on and minimize their cash outflow,” said Herb Tyson, ICSC vice president of state and local government relations. Examples of questions ICSC is asking: “Can we get some break in terms of timing of paying property taxes? Or can you pump the brakes on fees and penalties for late property tax payments?”

In New York state, taxes for properties worth more than $250,000 are due Jan. 1 and July 1, while taxes for properties worth less are due Jan. 1, April 1, July 1 and Oct. 1. There is no word yet on whether these tax deadlines will be postponed. Landlords in California — the first state to issue a public health shelter-in-place order, on March 10 — were required to meet an April 10 deadline to file their property taxes for the period of Jan. 1, 2020, through June 30. The tax date is established by state law, and only an act of the state legislature could have changed it. The counties of San Francisco, San Mateo and Kern, however, have extended their property tax deadlines until May 4.

California’s annual state budget is effective from July 1 to June 30 and is normally approved in June. The 2020-2021 state budget will see a significant revenue shortfall, given drastically reduced tax collections. Governor Gavin Newsom submitted a new budget proposal in January but that is now under review by state legislators. The bulk of property taxes collected by the state of California funnel back to the counties, and both the California State Association of Counties and the California Association of County Treasurers and Tax Collectors (CACTTC) had opposed an extension to the deadline. However, the CACTTC said counties could waive penalties, costs or other charges resulting from tax delinquency due to reasonable cause and circumstances related to the pandemic, but that would be on a case-by-case basis.

“Communication is going to be the key,” said O’Leary. “Tenant to landlord, landlord to lender and lender to local government. As I consult with small businesses and community leaders, I work hard to break through tribal mentalities and ask everyone to focus on the community as a whole.”

By Ben Johnson

Contributor, Commerce + Communities Today